Notebookventura@gmail.com

“You ever heard of the Taco Beat?”

I asked a young Hispanic newspaper reporter attending the National Association of Hispanic Journalists in Anaheim in 2013. He looked at me like a dog staring at a TV set before shaking his head.

We were talking about how journalism was changing but for him, not fast enough. So I told him about the “Taco Beat.”

More than two decades ago, many Hispanic newspaper reporters claimed they were hired only to add a little color to the newsroom and most of us were relegated to the “Taco Beat” as we liked to say back then.

Being cast to The Taco Beat meant Hispanic reporters were often assigned to cover the barrio, being sent on assignments only to translate for reporters who didn’t speak Spanish, or being sent more often across the border to cover Juarez.

As they say, “Baby, you’ve come a long way” I told this reporter.

The FBI and Ferguson

The “Taco Beat” came to mind while reading stories about FBI investigations into many recent civil rights violations, including the Department of Justice report that uncovered racist practices at the Ferguson Police Department and injustices of Ferguson Municipal Court.

The “Taco Beat” came to mind while reading stories about FBI investigations into many recent civil rights violations, including the Department of Justice report that uncovered racist practices at the Ferguson Police Department and injustices of Ferguson Municipal Court.

The FBI seems to be evolving as the Lone Ranger of policing the police across the nation – cleaning house with investigations, resulting in U.S. Department of Justice lawyers filing of civil rights lawsuits against police departments across the country including in the cities of Albuquerque, Cleveland, San Diego and New Orleans.

Since 2009, the Department of Justice with the FBI as its investigative arm has launched probes into 21 police departments in the U.S., according to Vocativ.

In the late 1980, however, Hispanic FBI agents complained that they were being disproportionately assigned to what they described as the “Taco Circuit” and the “Tortilla Circuit,” which were terms used by agents to the bureau’s involuntary 30 to 90 day involuntary wiretap assignments.

They claimed the FBI was engaging in wholesale discrimination against them.

The denials rained down: Critics and FBI bosses adamantly denied the allegations, saying that the agency is fair in its treatment of Hispanic agents. The FBI officials repeatedly justified some of the practices and policies by citing “the needs of the bureau.”

But in 1988, the nation’s chief civil rights investigative branch got a black eye.

In a ruling in a class-action discrimination initially filed by 331 agents from across the nation, a federal judge ruled that the FBI engaged in a pattern and practice of discrimination against Hispanic Agents.

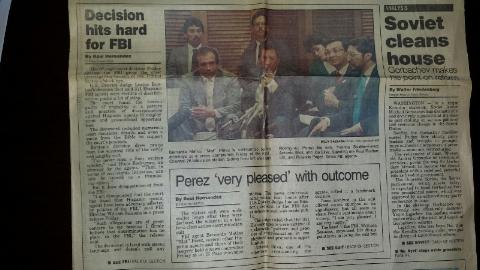

U.S. District Court Judge Lucius Bunton packed his ruling with strongly worded language, including a passage of “love thy neighbor as thyself” Bible quote. He described the bureau’s Equal Employment Opportunity system as “deficient” and in “serious need of revision,” a story I wrote on Oct. 1, 1988 stated.

The judge said Hispanics shouldn’t be “Anglo helpers” – used as translators for non-Spanish speakers.

The FBI Director William Sessions said there would be reform.

“I’ve never seen a finer written opinion,” Hugo Rodriguez, an attorney for the plaintiffs, said in my interview with him.

The FBI Lawsuit Got Nationwide Coverage

In a story in the New York Times in 1988, Hispanic agents testified about the ugly side of the FBI

In a story in the New York Times in 1988, Hispanic agents testified about the ugly side of the FBI

“Louis Barragan, an agent from Sarasota, Fla., testified that he had heard white agents refer to Hispanic colleagues as ‘lazy spics,’ ‘dirty Mexicans’ and ‘lazy Mexican wetbacks.’ A new agent, Alba Lorena Sierra, said she was told by supervisors in her training that she looked ”too ethnic” and should buy Vogue magazine for tips on hair styles,” according to the NYT story.

In 1988, The FBI had hiring numbers that rivaled those of Ferguson Missouri police department. In 2014, Ferguson had two black cops on its police force of 52 cops. The FBI wasn’t far behind back then, according to the New York Times.

While about 4 percent of the bureau’s 9,600 agents are Hispanic, only one of the heads of the 58 field offices is, according to bureau figures, the NYT reported. Figures for 1987 say that there were only six Hispanic agents among the bureau’s 440 highest-ranking agents, the newspaper stated.

The number of Hispanic agents who have joined the lawsuit is at issue. The bureau says it is 255; the plaintiffs say 311. But whatever the figure, ”How can so many of them be wrong about what goes on at the F.B.I.?” asked Antonio V. Silva, one of the plaintiffs’ lawyers, according to the NYT’s story.

Fast-Foward – Translating for Amber in El Paso

“Bob, what’s the idea of assigning me to translate for Amber Smith? That was an insult of the highest degree. Bob, if you want someone to cover a story with Spanish speakers, then assign it to me or one of the other Chicano reporters,” an angry reporter Joe Olvera told Bob Locke, the El Paso Times city editor.

“But never, ever again assign me to be an Anglo helper because I am no such thing. I am a legitimate journalist, reporter and columnist with tons of experience…” Olvera told Locke.

Joe wrote about this in his 2007 book, “Chicano – Sin Fin! – Memoirs of a Chicano Journalist.

Joe Olvera, a very good friend, columnist and journalist, loved to rattle cages at the newsroom. I loved watching him do it, all 6-foot, three-inches of him. Joe was vociferous, especially when standing in the middle of the newsroom ranting, mumbling and voicing his discontent.

He worked at both the Herald-Post and the El Paso Times like I did.

However, I was a rookie newspaper reporter and unlike Joe, I would wash cars, pick up dry cleaning or babysit white kids to keep working in the newsroom. When I landed a job at the El Paso Herald-Post, I thought I had died and gone to heaven. I even sucked up my pride big time and became an “Anglo helper” too, a newsroom “translator.”

Once, I was sent to translate for Herald-Post reporter Jim Braden who had to do features story in Juarez.

While we were in Juarez, the story broke that they arrested the Rio Grande strangler who had killed several Mexican woman along the river. I was smart enough to know that this was way over Jim’s puff-piece writing. So I jumped on it. I told Jim, “I got this.”

He gladly agreed to let me cover a Mexican police press conference while we were in Juarez I wrote the story, and the editors loved it.

As my confidence and my experience grew in the newsroom, I gradually became a little more vocal, a little more assertive.

Joe sometimes complained about the assignments he got including going to Mexico with reporter Peter Copeland and Photographer Ruben Ramirez to find out who killed a Colorado college professor in Sinaloa, Mexico and getting smuggled across the border inside a car trunk and then, traveling to Chicago where he found a job washing dishes.

Adding insult to injury, Editor Harry Moskos said he was sending Joe to Mexico because he was a big guy, and Copeland because he was the “ace reporter.”

“I am sending Copeland because he is an ace reporter, and I am sending Ramirez because he is the chief photographer. Olvera, I am sending him because he is so big,” Joe wrote in his book that Moskos told another editor.

Joe also did an investigative piece about a thug, turned corrupt notary public ,who was ripping off illegal immigrants. Joe posed as an illegal immigrant and used a secret tape recorder during an office visit with the notary public.

Hispanic reporters didn’t mind writing these stories but the long, investigative projects along with the plum beats such as city hall, county government and the courts were usually given to white reporters.

These were the stories that would get reporters noticed through writing awards. The stories would look good on resumes that land better reporting jobs at bigger newspaper.

The Newsroom “Monsters” Come to See Joe

Joe, who grew up in the mean streets of El Paso, wrote about this notary public in his book.

He described when “two monsters” came into the newsroom to talk about the notary public story. Joe, the Editorial Page Editor Angela Hogue and I shared small room at the Herald-Post newsroom.

Angela was in her own world. She once applied for membership in the El Paso Chapter of Daughters of the British Empire and was rejected. She said she wasn’t British enough.

I joked with Joe and told him that we had both been vanquished to newsroom hell by sharing a large closet with three large desks and Angela. But that is another story.

Angela wasn’t in the room when the two guys arrived.

Anyway, the two guys looked serious. I looked at Joe, he was a bit nervous as the two guys stood over his desk. They didn’t appear happy. They asked if he was Joe Olvera. He said yes and casually stood up. I had a bogus smile, casually walked and stood by him like we were BFF.

I’m thinking that this is going to get ugly, very fast and very soon.

We were both relieved that the two guys smiled, wanted to shake his hand and thank him for exposing the notary public who was cheating people out of thousands of dollars by making false promises about getting them legal status in the U.S. and offering to smuggle others in the country.

The two guys left. Joe and I grinned and burst out laughing after the two had left the building. But the two left their calling card, so to speak:

“If you ever need anything, if anyone ever tries anything funny with you, aqui tienes dos Carnales. Don’t hesitate to call us because we don’t like what those assholes are doing to our people,” Joe wrote that one of the guys told him before leaving.

The terms “Taco Beat” and “Taco Circuit” Are Gone, But…

Although the terms “Taco Beat” and “Taco Circuit” appear to have faded in newsrooms and at the FBI, there is still a long way to go but I’m cautiously optimistic.

If the “best law enforcement agency in the world,” as Judge Bunton described the FBI in his 1988 ruling, cleaned up its house and is now going to rogue police departments and kicking ass and taking names, there is hope.

Diabetes and an Attitude

Diabetes ravished Joe’s body and put him in a wheelchair. His body is frail but his voice through his columns is strong, cantankerous. Sometimes, he emails and ask what I think about this missive or that one. Some I like a lot ; others, well, we’ve exchanged a few passionate and opinionated emails.

In my later newsroom years, I unashamedly got an attitude, some argue a chip on my shoulder: “What? Do I look like your gardner? Do you see a leaf blower in my hand? Am I your bitch, today?”

You’ve come a long way baby!