SAN DIEGO

A Los Angeles furniture business and its owner plead guilty Tuesday to smuggling endangered abalone and Totoaba that could be sold for millions of dollars in China, officials said.

A Los Angeles furniture business and its owner plead guilty Tuesday to smuggling endangered abalone and Totoaba that could be sold for millions of dollars in China, officials said.

The owner of Kaven Company, Inc.’s Kam Wing Chan used the business, which imported Asian furniture, to buy endangered fish in Mexico, import them into the United States and then export them to Asia, officials said.

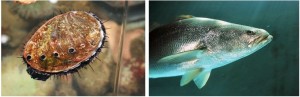

Chan admitted in her guilty plea that on one occasion on October 9, 2013, he smuggled into the United States 37 pounds of dried abalone (including the endangered white and black abalone) and 58 Totoaba swim bladders, which had been purchased in violation of Mexican law.

Chan is facing a sentence of up to 20 years in custody.

The seafood was then illegally exported to companies owned by one of Chan’s relatives in China. Both abalone and Totoaba are prized in Asia where they are considered “culinary delicacies,” and often adorn the buffets of festival meals and are served at formal dinners, according to officials.

The defendants agreed to forfeit the smuggled wildlife and make restitution to the government of Mexico in the total amount of $55,000 for the loss of the natural resource, and pay fines totaling $14,500, officials said.

The case was investigated by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Office of Law Enforcement and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Office of Law Enforcement

Officials provided background information about the endangered fish in question:

Totoaba macdonaldi, also known as Cynoscion macdonaldi, is a species of marine fish. It can grow to more than 6½ feet in length, weigh up to 220 pounds, and live up to 25 years. This marine fish is the largest species within the scaienidae family.

It is endemic only to the Gulf of California, the narrow inlet between Baja California and the Mexico’s mainland (also called the Sea of Cortez).

During the Totoaba’s spawning season, which runs from approximately March to May each year, Totoaba fish travel to the shallower waters at the mouth of the Colorado River, making them vulnerable to commercial and sport fishermen.

Totoaba fish have internal air bladders that help them control their buoyancy in water. These air bladders, also called swim bladders, are highly prized in Asia for a variety of uses: as an ingredient in a specialty soup, for perceived therapeutic and medicinal purposes, and to improve the complexion.

Swim bladders from the endangered Totoaba fish can be identified by distinctive tubes that are attached to the bladders. Totoaba fish are protected as an endangered species under the Endangered Species Act and the Lacey Act, and the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora or CITIES.

These laws generally prohibit the taking, possessing, transporting, importing, sale, and trade of Totoaba fish.

Based on information law enforcement officers have developed from conversations with researchers in Mexico and Totoaba fish smugglers, the value of Totoaba swim bladders in Mexico is approximately $1,500-$1,800 each.

Once imported into the United States, the value increases to $5,000 each. They can be resold for $10,000 to $20,000 apiece in the overseas market.

As it is not legal to fish for Totoaba in Mexico, a poacher cannot risk being caught in possession of the easily-identified body of the endangered fish. It is much simpler to transport only the bladder, which is lighter, smaller, and much more valuable. As a result, PROFEPA — the Mexican federal agency tasked with the protection of endangered species — reports encountering Totoaba taken from the Colorado River, carved open so their swim bladders can be removed, and left to die on the shores.

Background on White Abalone:

White abalone (Haliotis sorenseni) are herbivorous gastropods (the same taxonomic class as snails and slugs) that live in rocky ocean waters. Their shell is oval-shaped and very thin.

The bottom of their feet is orange, and the epipodium (a sensory extension of their foot that has tentacles) is a mottled orange-tan. They are generally 5-8 inches long, but can grow to as big as 10 inches.

They weigh about 1.7 pounds on average. They were the first marine invertebrate to be listed as endangered under the ESA.

Due mainly to overfishing, there has been a 99% reduction in white abalone density since the 1970’s.

Once occurring in numbers as high as 1 per square meter of suitable habitat, recent surveys show that densities average 1 per hectare in the Channel Islands off southern California.

Although historically there have been millions of white abalone off our coast, recent studies suggest that the current population is approximately 1,600-2,500 individuals.

Unfortunately, adults do not occur in high enough densities to successfully reproduce, contributing to repeated recruitment failure and an effective population size near 0.

Background on Black Abalone:

Black abalone (Haliotis cracherodii) are large marine gastropod mollusks found in rocky intertidal and subtidal habitats. Both their “mantle” and “foot” are black.

They have 5-9 open respiratory pores along the left sides of their shell and spiral growth lines on the rear. Their tentacles (surrounding their foot and extending out of their shell) sense food and predators.

Black abalone are herbivores. They primarily eat giant kelp and feather boa kelp in southern California, south of Point Conception habitats, and bull kelp in central and northern California habitats.

Black abalone commercial fishing peaked in 1973 at 868 metric tons (nearly 2 million pounds).

By 1993, both commercial and recreational fisheries for black abalone closed. Black abalone have experienced significant declines in abundance and have gone locally extinct in most locations south of Point Conception, CA.

Increasing distance among spawning males and females has led to reproductive failure as population density decreases.

In addition to disease, black abalone face challenges due to elevated water temperature caused by the thermal discharge of power plants.

Other factors responsible for the decline of black abalone are illegal harvest and habitat destruction. Natural predation by a variety of predators (sea stars, the southern sea otter, and striped shore crab) as well as competition with purple and red sea urchins for space also threaten their survival.