BY RAUL HERNANDEZ

The U.S. Army sergeant with the rainbow of medals on his chest that looked like a Jackson Pollock painting came into my apartment in El Paso decades ago. He stood in the middle of the living room and stared at the large, upside-down American flag on the wall and curled his lip in disgust.

The U.S. Army sergeant with the rainbow of medals on his chest that looked like a Jackson Pollock painting came into my apartment in El Paso decades ago. He stood in the middle of the living room and stared at the large, upside-down American flag on the wall and curled his lip in disgust.

“What the hell is that?” he said, slowly shaking his head.

“A flag,” I said calmly.

“I know it’s a goddamn flag but what’s it doing upside down?”

“I put it that way. When a nation or a ship is in distress, it puts its flag upside down,” I said.

The U.S Army soldier, who had two tours of Vietnam and looking at a third down the road, muttered some curse words.

“You’re a communist hippie agitator, Rudy. Always protesting some shit,” he said, trying to sound upset with a straight face.

When his career ended, Ignacio Medina would hold the highest rank as a non-commissioned officer in the army, command-sergeant-major at Fort Bliss. He earned the Silver Star for bravery in Vietnam. But Medina also knew I had a right to protest the Vietnam War. I was in America, and whats more, I had also served my country in Vietnam at Phan Rang A.B. in 1971-1972 with the U.S. Air Force.

Besides, Medina’s stepson, my roommate and best friend, Art Molina, never had a problem with my upside-down American flag. Art was a machine gunner aboard a Huey helicopter in the Central Highlands of Vietnam. The first time Art saw my upside-down flag on the wall, he smiled and said. “I like it, Buddy.”

Besides, Medina’s stepson, my roommate and best friend, Art Molina, never had a problem with my upside-down American flag. Art was a machine gunner aboard a Huey helicopter in the Central Highlands of Vietnam. The first time Art saw my upside-down flag on the wall, he smiled and said. “I like it, Buddy.”

My father, Juan Hernandez, who served in three wars like Medina with the U.S. Army — World War II, Korea and Vietnam — had no problem with my upside-down flag or my protest. My father was proud of his Bronze Star and Combat Infantry Badge.

When I was in Vietnam, I wrote to then El Paso Congressman Richard White asking his office to mail an American flag that’s flown over the capitol. I got my flag in 1971, and still have White’s letter stating that the flag flew over the nation’s capitol and thanking me for my service.

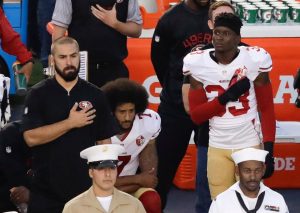

Sunday, the NFL season opened with peaceful demonstrations during the national anthem, players trying to draw attention to the number of unarmed blacks shot by police across the nation. San Francisco 49ers backup quarterback Colin Kaepernick began the protests by sitting on the bench and later, kneeling on one knee.

Kaepernick isn’t advocating firebombing buildings, looting, burning the flag, violence or encouraging people to blow up buildings or kill people. But his protest has ignited criticism of his silent gesture .

However, there has also been much support, including praise from soldiers and military veterans.

The critics say that out of respect for the 911 victims, the players shouldn’t protest. Well, the argument could be made that the protests shouldn’t be held out of respect for Veterans Day, Pearl Harbor Day or another day to honor Americans who died in wars and terrorist attacks.

Everyday is a good day for peaceful protests in America, and even if we disagree with the message or causes or where or how people demonstrate, it is their constitutional right to do so.

The streets were full of protestors during the Vietnam War, and many argue that this caused America to pull its troops out of that country faster or the Vietnam War Memorial could have been longer with more names chiseled on it.

Other players including Denver Broncos’ Brandon Marshall have followed suit with Kaepernick.

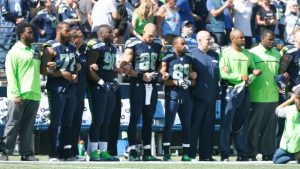

On Sunday, the Kansas City Chiefs locked arms during the anthem, and cornerback Marcus Peters raised his fist into the air. The Seattle Seahawks team locked arms at Sunday’s season opener against the Miami Dolphins.

While people may not understand it or disagree with the way the players and others are protesting, they should respect the demonstrations.

While people may not understand it or disagree with the way the players and others are protesting, they should respect the demonstrations.

But there is usually a price to pay for any protest.

The person in America who epitomizes what price there is to pay when you take a stand against social injustices once said this:

“The hottest places in hell are reserved for those who in a period of moral crisis maintain their neutrality.” — Martin Luther King Jr.

America has survived many protests throughout history. It will not crumble because Kaepernick, Marshall or others kneeled, sat or lock arms during the anthem.

Marshall paid a price for what he did. He lost a sponsor. Kaepernick put his money where his mouth is by giving $1 million to poor communities. The Twitter buzz line has lit up with criticism against him, including racial slurs being tossed into the rants of bigots.

I don’t know if I would have demonstrated the same way Marshall, Kaepernick or other players. But I admire them along with Black Lives Matters protestors and others who have the courage to stand up against the high number of fatal-shootings by cops of unarmed blacks, minorities and others.

In 2016, so far, police have killed 754 people — many of whom were unarmed, mentally ill, and people of color, according to the Guardian newspaper.

When I got home from Vietnam, the protesters were out in full force at Travis Air Force Base, waving their signs and yelling their chants: “Hell, No! We Won’t Go!”

I knew I was back home when another Vietnam veteran greeted me at the El Paso International Airport, my Dad, “Welcome home, mi hijo.”

My father and Mr. Medina are both buried at Fort Bliss National Cemetery with honor and plenty of medals earned in the service of their country.

I believe they would have also approved of what Kaepernick, Marshall and others are doing to make this country better.

After all, this is America. That’s what we are all about.