In this clip from Explorer, Scott Pelley and Nick Schifrin discuss fake news and the state of the media.

“It gets at the extent to which people rely on intuitive answers that pop to their mind as opposed to reflecting and checking whether the answer that comes to mind is right or wrong,” says Steve Sloman, a professor of cognitive science at Brown University and editor-in-chief of the journal Cognition.

And in a world where misleading news stories are the new norm, the Moses ark question is a good predictor of whether people are susceptible to fake news. Such is the illusion of explanatory depth, or our tendency to overestimate our understanding of how something works.

It is rooted in our tendency—or lack thereof—to reflect and to double check, Sloman says.

But it’s not always easy to discern factually inaccurate news stories, and we can thank human nature for our propensity to accept what we read without much question or reflection.

In a recent article for The New Yorker, journalist Elizabeth Kolbert reviews several studies on the human mind’s limitations of reason, starting with groundbreaking work at Stanford 50 years ago.

“Coming from a group of academics in the nineteen-seventies, the contention that people can’t think straight was shocking,” Kolbert writes. “It isn’t any longer. Thousands of subsequent experiments have confirmed (and elaborated on) this finding.”

What Causes the Logic Breakdown?

There are a number of ways in which reason fails us, leaving us vulnerable to factually incorrect news stories that spread like viruses and infect understanding of what’s real and what’s not. One of the relevant psychological concepts is “motivated reasoning,” writes Adam Waytz, an associate professor of management and organizations at Northwestern’s Kellogg School.

Motivated reasoning is the idea that we are motivated to believe whatever confirms our opinions.

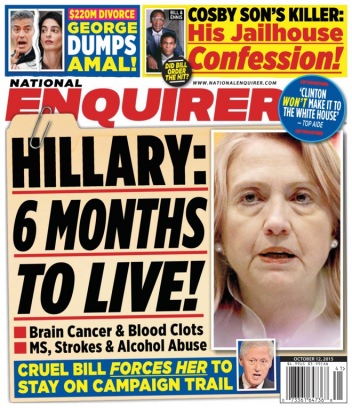

“If you’re motivated to believe negative things about Hillary Clinton [or Donald Trump], you’re more likely to trust outrageous stories about her that might not be true,” Waytz says. “Over time, motivated reasoning can lead to a false social consensus.”

Another related concept is “naïve realism,” or the idea that our views are the only ones that are accurate. Such a notion contributes to polarization in political discussions; instead of disagreeing with people, Waytz says, we often dismiss their views as incorrect.

“We’re all quick to believe what we’re motivated to believe, and we call too many things ‘fake news’ simply because it doesn’t support our own view of reality,” he notes.

Sloman’s research focuses on the idea that knowledge is contagious. Hence his book title: The Knowledge Illusion: Why We Never Think Alone.

Sloman recently published a paper called “Your Understanding Is My Understanding” in the journal Psychological Science with Brown undergraduate Nathaniel Rabb. In the web-based experiment, which examined more than 700 volunteers, Brown and Rabb made up a phenomena in which scientists supposedly discovered a system of helium rain.

In one situation, they told the volunteers that the scientists do not fully understand the phenomena and cannot fully explain it, before asking the volunteers to rate their own understanding of helium rain on a scale of one to seven, with one being the lowest. Most of the volunteers rated their answers at one, admitting they don’t understand the concept.

However, in the second instance, Sloman and his partner told the volunteers that the scientists understand helium rain and can fully explain how it works. When asked to rate their own understanding, this group of volunteers submitted answers that averaged around two. The fact that the scientists understand gave the volunteers an increased sense of understanding, Sloman says.

The idea can easily be translated into politics.

“It’s like understanding is contagious,” Sloman says. “If everyone around you is saying they understand why a politician is crooked, they saw a video [about that person] on YouTube…then you’re going to start thinking that you understand, too.”

How to Fight Fakeness

With all this research shedding light on what makes us so susceptible to fake news, is there a way we can protect ourselves against it?

“I don’t think it’s possible to train individuals to verify everything that they encounter,” Sloman says. “It is just too human to believe what you’re told and move on.”

However, Sloman says he sees the potential in training a community to care about verification. Think of the headlines and stories that are shared on your Facebook feed every day that, most likely, align with your world view. We as a community should consider lowering the bar on what should be double-checked, Sloman says.

All it takes is one person to comment that something doesn’t add up.

“Develop a norm in your community that says, ‘We should check things and not just take them at face value,’” Sloman says. “Verify before you believe.”