We now take more pills than ever. Is that doing more harm than good?

If you’re like most Americans, you probably start your day with a hot shower, a cup of coffee—and a handful of pills.

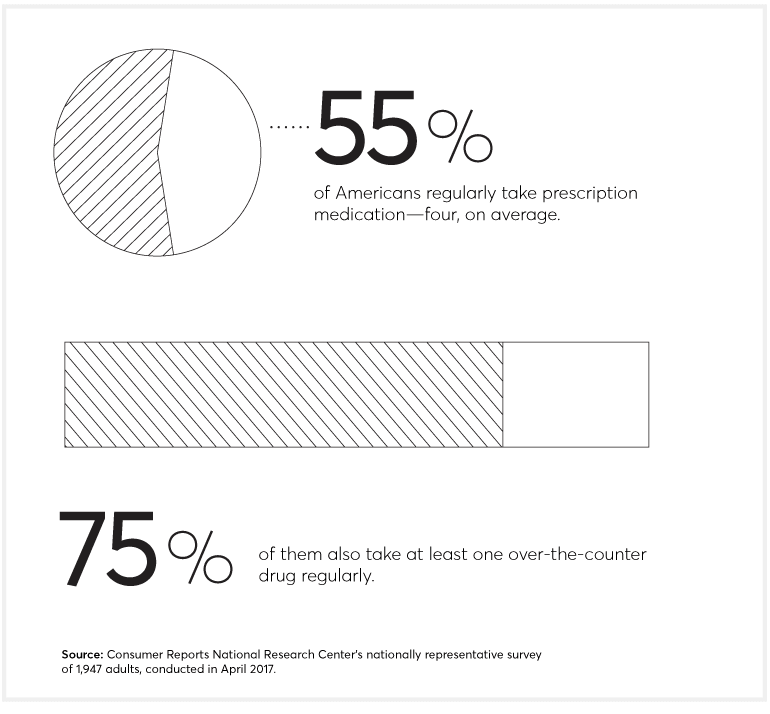

More than half of us now regularly take a prescription medication—four, on average—according to a new nationally representative Consumer Reports survey of 1,947 adults. Many in that group also take over-the-counter drugs as well as vitamins and other dietary supplements.

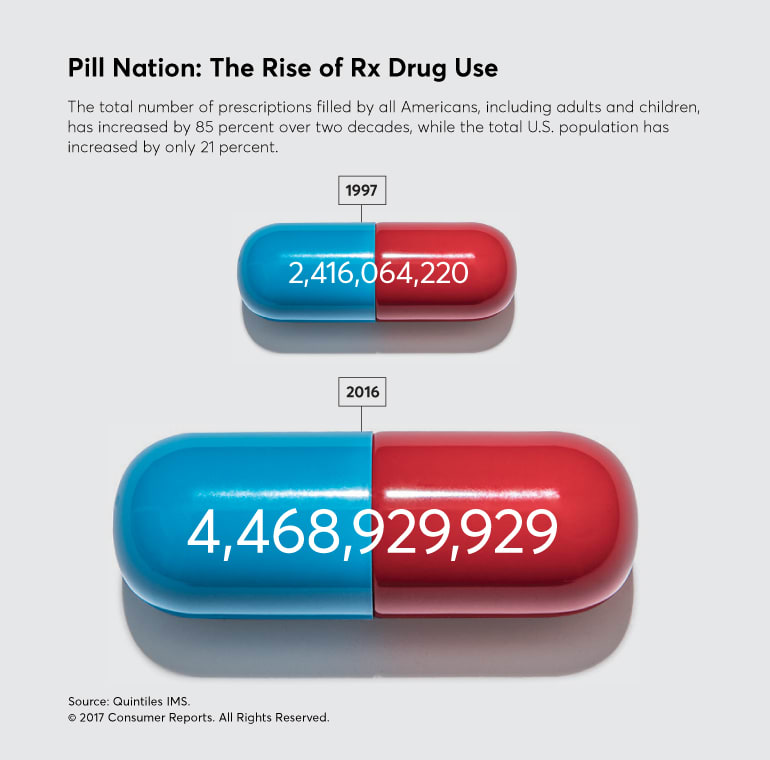

It turns out Americans take more pills today than at any other time in recent history (see “Pill Nation: The Rise of Rx Drug Use”)—and far more than people in any other country.

Much of that medication use is lifesaving or at least life-improving. But a lot is not.

The amount of harm stemming from inappropriate prescription medication is staggering. Almost 1.3 million people went to U.S. emergency rooms due to adverse drug effects in 2014, and about 124,000 died from those events. That’s according to estimates based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Food and Drug Administration. Other research suggests that up to half of those events were preventable.

All of that bad medicine is costly, too. An estimated $200 billion per year is spent in the U.S. on the unnecessary and improper use of medication, for the drugs themselves and related medical costs, according to the market research firm IMS Institute for Healthcare Informatics.

Our previous surveys have found that higher drug costs—including more expensive drugs and higher out-of-pocket costs—also strain household budgets, with many people telling us they had to cut back on groceries or delay paying other bills to pay for their prescriptions.

The nation’s expensive and harmful pill habit comes in several forms:

Taking too many drugs. Nicole Lamber of Williamsburg, Va., says she became “completely nonfunctional”—with pain, rashes, diarrhea, and anxiety—from the adverse effects of several drugs, including some her doctors prescribed to treat side effects from her initial prescriptions.

Taking drugs that aren’t needed. Jeff Goehring of Waukesha, Wis., suffered a debilitating stroke shortly after he began taking testosterone, which his doctor prescribed for fatigue even though the Food and Drug Administration hadn’t approved it for that use, according to a lawsuit he’s involved in.

Taking drugs prematurely. Diane McKenzie from Alsip, Ill., had regular bouts of diarrhea and vomiting, side effects she attributed to the drug metformin, which her doctor prescribed for “prediabetes,” or borderline high blood sugar. But McKenzie found that losing weight controlled her blood sugar levels without drugs.

Why would so many people take so many potentially harmful pills?

Partly because while all drugs pose some risks, they’re often essential, treating otherwise deadly or debilitating diseases, notes Andrew Powaleny, director of public affairs for the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA), a trade group.

To be sure, some people—especially those who are uninsured or underinsured—don’t get all of the care they need, including medication.

Still, many Americans—and their physicians—have come to think that every symptom, every hint of disease requires a drug, says Vinay Prasad, M.D., an assistant professor of medicine at Oregon Health & Science University. “The question is, where did people get that idea? They didn’t invent it,” he says. “They were spoon-fed that notion by the culture that we’re steeped in.”

It’s a culture, say the experts we consulted, encouraged by intense marketing by drug companies and an increasingly harried healthcare system that makes dashing off a prescription the easiest way to address a patient’s concerns.

To investigate this growing problem and to help you manage your drugs, we sought expert advice on how to work with doctors and pharmacists to analyze your drug regimen. We reviewed the drug lists submitted by 20 Consumer Reports readers to see whether we could find problems, and alerted them when we did. We also dispatched 10 secret shoppers to 45 drugstores across the U.S. to see how well pharmacists identify potentially problematic drug interactions. And last, we compiled a list of 12 conditions that are often first treated with drugs—but usually don’t need to be.

A Growing Tide of Risk

Nicole Lamber’s problems started with a single prescription medication when, stressed in her first job as a physician’s assistant, a physician colleague prescribed alprazolam (Xanax). “I wasn’t given any warning about anything at all, it was just presented as a safe drug,” she says. Within a few months, Lamber, who is now 38, was depressed, even suicidal. “It scared me,” she remembers.

Over the next five years, Lamber says she saw a series of doctors who prescribed more and more drugs: the ADHD medication Adderall to lift her mood and help her focus; another to counter the side effects of that drug; others to improve her appetite and help her sleep; and when her anxiety worsened, another sedative.

The combination, she says, made her so ill she couldn’t leave the house. “I saw tons of specialists,” she recalls. “A gastrointestinal doctor for chronic diarrhea, an orthopedist and rheumatologist for joint pain, a dermatologist for rashes. None of them questioned my list of meds.”

Lamber’s story is hardly unique: The percentage of Americans taking more than five prescription medications has nearly tripled in the past 20 years, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. And in our survey, over a third of people 55 and older were taking that many drugs; 9 percent were taking more than 10.

In some cases, multiple drugs are “completely appropriate,” says Michael Hochman, M.D., of the Keck School of Medicine at the University of Southern California. But as the number of drugs piles up, so does the need for caution. “The risk of adverse events increases exponentially after someone is on four or more medications,” he says.

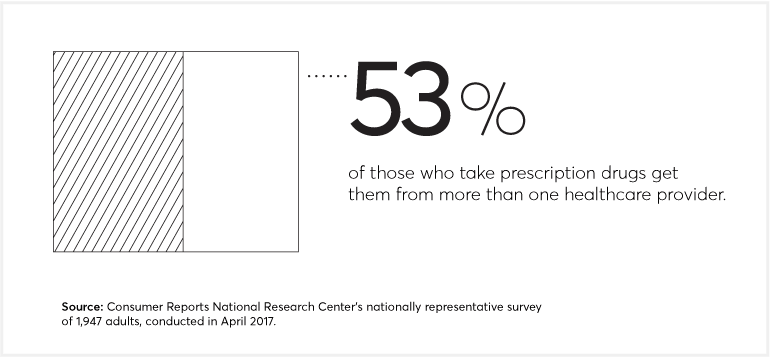

That’s especially true when multiple doctors are involved. Poor communication between providers often contributes to drug errors, says Michael Steinman, M.D., at the University of California, San Francisco School of Medicine. And seeing more than one doctor is now the norm: 53 percent of those in our survey taking prescription medications said they received them from two or more providers.

Potentially harmful prescribing is all too common, says Steven Chen, Pharm.D., an associate dean for clinical affairs at the University of Southern California School of Pharmacy, who worked with Consumer Reports to review the medication lists submitted by readers. (Chen, like many pharmacists reviewing drugs, didn’t have access to medical records.) Of the 20 lists he reviewed, only two received a clean bill of health. Among the other 18, Chen identified 38 potential problems, half of which he considered serious. They included one person taking a combination of blood-pressure drugs that could cause potassium levels to spike and trigger dangerous heartbeat abnormalities, and another’s mix of a blood thinner, a pain reliever, and baby aspirin that could cause stomach bleeding.

Identifying those kinds of risks and untangling potential harmful interactions can be difficult.

For Lamber, it meant finding a doctor who was willing to help. Still, stopping the drugs was a long, “nightmarish” process, she says, because she had become physically dependent on them and it triggered painful withdrawal symptoms. Today, while some side effects linger, she says she feels lucky to be alive. “The drugs—and the withdrawal from them—almost killed me,” she says.

Selling Sickness

Jeff Goehring, now 55, ran a busy deli and snow-plowing business in 2009 when he says he started feeling more tired than usual. He decided to see a doctor who, he says, prescribed AndroGel, a drug containing the male hormone testosterone.

Goehring says he didn’t know then that testosterone drugs are approved by the FDA only for men with hypogonadism, or very low levels of testosterone, usually caused by infection, injury, or other health problems. He also says he wasn’t warned that testosterone increases the risk of a heart attack or stroke, according to the FDA.

After four days applying the drug, Goehring suffered a stroke, according to a lawsuit he is part of against AbbVie, AndroGel’s maker. He’s one of more than 6,000 people nationwide suing six drug companies that make testosterone products, claiming that they suffered a heart attack, stroke, or other cardiovascular event after using one of the drugs.

In a statement to Consumer Reports, AbbVie said the company believes “our disease education and marketing of AndroGel have adhered strictly to FDA-approved uses,” and emphasized that it’s up to each physician to make sure the drug is used for appropriate purposes.

So why would Goehring’s doctor put him on a medication that may not have been indicated for his condition? For one thing, doctors can prescribe drugs for such off-label uses even if the FDA hasn’t reviewed the evidence and approved the drug for those purposes, explains Stephanie Caccomo, a spokeswoman for the agency.

For another, about the time Goehring started on testosterone, pharmaceutical companies began investing heavily in ads for the drugs and even came up with a catchy new name: “low T.” Spending on the ads rose quickly, to $153 million in 2013. And companies got a lot of bang for their advertising buck. A March 2017 study in JAMA found that between 2009 and 2013, men exposed to more TV ads for testosterone or “low T” were much more likely to wind up on the drug.

Those “low T” figures are a drop in the bucket. Total spending on drug ads targeting consumers reached $6.4 billion last year, 64 percent more than in 2012, according to Kantar Media, a market research company. That’s $1.3 billion more than the FDA’s entire 2017 budget. Drug companies spend even more—$24 billion in 2012 alone—on marketing just to doctors through ads in medical journals, face-to-face sales, free medication samples, and educational and promotional meetings, according to a report from the Pew Charitable Trusts.

Building relationships with healthcare providers and marketing medicines is valuable, says Powaleny, the spokesman for PhRMA, helping to ensure “that healthcare professionals have the latest, most accurate science-based information available regarding prescription medicines.”

But many drug-safety experts worry that the practice also contributes to overmedication.

“Low T is a marketing term intended to sell testosterone as a kind of fountain of youth,” says Steven Woloshin, M.D., a professor at the Dartmouth Institute of Health Policy and Clinical Practice. For most men, he says, testosterone “declines naturally with age,” and research shows that taking drugs to compensate has “little or no benefit” and “some serious risks.”

That’s something Goehring wishes he had understood better. His stroke, he says, still impairs his short-term memory and has left one of his hands partially numb, forcing him to close his deli. Now, eight years later, he’s still trying to pay off hospital bills not covered by insurance.

The Rise of ‘Predisease’ Diagnoses

Two years ago, Diane McKenzie’s doctor recommended metformin (Glucophage) to treat a blood sugar level that put her at the high end of normal but still below the cutoff for diabetes. Concerned about developing the full-blown disease, McKenzie, then 44, agreed to take it. But almost immediately, she began to suffer from diarrhea and vomiting, known side effects.

Her experience illustrates another trend that’s putting more people on drugs: diagnosing them in the “predisease” stage of a condition. For example, identifying people with mild bone loss (osteopenia, or preosteoporosis), slightly elevated blood pressure (prehypertension) or, as in McKenzie’s case, prediabetes, a slightly elevated—but still normal—blood glucose reading.

Catching disease early, of course, can be a good thing if it helps you address a problem before it leads to serious harm.

But “lowering the bar for what’s considered normal” can also get people on drugs before they need to be, says Allen Frances, M.D., a professor emeritus at Duke University who studies how the medical profession sometimes expands the definition of diseases. And treating people with drugs at the very early stage of a condition “often harms more people than it helps,” Frances says.

That’s what McKenzie, a nurse practitioner, says she worried about when she began experiencing side effects. After a few months, they were so intolerable she stopped taking metformin.

Research actually supports that approach. A 2015 study in Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology found that for people with prediabetes, regular exercise plus a low-calorie, low-fat diet cut the incidence of developing type 2 diabetes by 27 percent; metformin lowered it by 18 percent. And the side effects of exercise and a healthy diet are other health benefits, not diarrhea and vomiting.

McKenzie decided to make lifestyle changes to lower her blood sugar. Key to her success, she believes, is the stray puppy she adopted, who motivated her to take long daily walks, helping her lose 70 pounds. Today McKenzie’s blood sugar levels are under control.

Doctors Who Know When to Say No

Ranit Mishori, M.D., a professor of family medicine at the Georgetown University School of Medicine in Washington, D.C., made it her New Year’s resolution this year to prescribe fewer drugs.

She’s part of a trend called “de-prescribing,” or focusing on keeping patients healthy by getting them off unnecessary drugs. “In med school we’re taught how to prescribe, not how to take people off drugs,” she says.

Another doctor who de-prescribes is Victoria Sweet, M.D., who spent 20 years at a charity hospital in San Francisco with few high-tech resources but lots of time for patients. “There’s a big push in our country to practice medicine as if we are fixing machines with a broken part,” says Sweet, author of a forthcoming book, “Slow Medicine: The Way to Heal.” “Take the pill, fix the symptom, move on,” she says. “Slow medicine” means “taking time to get to the bottom of what’s making people sick—including medications in some cases—and giving the body a chance to heal.”

Some groups are trying to help that approach go mainstream. Through the Choosing Wisely initiative (Consumer Reports is a partner), more than two dozen medical organizations have made recommendations that involve dialing back the use of unneeded drugs.

And some medical organizations, such as the American College of Physicians, now advise doctors to try nondrug approaches first for certain conditions. For example, the ACP recommends usually treating back pain first with massage, spinal manipulation, or other nondrug options.

But for the system to change, insurance needs to evolve, too, says Cynthia Smith, M.D., vice president of clinical programs at the ACP. “A patient’s out-of-pocket costs are currently significantly less with medical therapy” than with nondrug options, she notes. “We need to make it easier for both doctors and patients to do the right thing.”

Kicking the Drug Habit

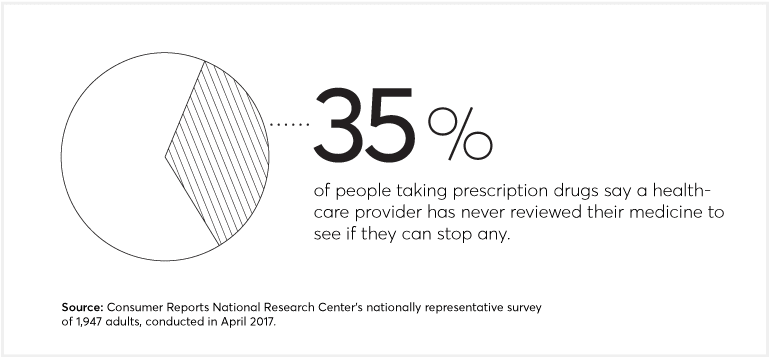

Talking with your doctor about whether you might feel better on fewer pills is well worth the effort. Half the people in our survey who take medication said they had talked with a doctor about stopping a drug, and more than 70 percent said it worked. When extrapolated to all U.S. adults, we calculate that comes to nearly 45 million fewer prescriptions. Here are tips on how to cut back on unneeded meds:

• Don’t cut back or stop taking a drug without first discussing it with your doctor. See “How to Get Off Prescription Drugs.”

• Have a comprehensive drug review with your doctor or pharmacist at least once per year. See “Give Your Drugs a Checkup: Reviewing Your Medication List Can Prevent Errors.”

• Give a family member and all of your healthcare providers a current list of your drugs. See “From Pill Organizers to Apps, How to Manage Your Meds.”

• Consider nondrug options first for many common health problems. See “12 Times to Try Lifestyle Changes Before Medication.”

—Additional reporting by Rachel Rabkin Peachman and Ginger Skinner

Editor’s Note: This special report and supporting materials were made possible by a grant from the state Attorney General Consumer and Prescriber Education Grant Program, which is funded by a multistate settlement of consumer fraud claims regarding the marketing of the prescription drug Neurontin (gabapentin).

This article also appeared in the September 2017 issue of Consumer Reports magazine.