What do Denmark, Costa Rica, and Singapore have in common? Their people feel secure, have a sense of purpose, and enjoy lives that minimize stress and maximize joy. Here’s how they do it.

What do Denmark, Costa Rica, and Singapore have in common? Their people feel secure, have a sense of purpose, and enjoy lives that minimize stress and maximize joy. Here’s how they do it.

This story appears in the November 2017 issue of National Geographic Magazine.

Who is the world’s happiest person?

It may be Alejandro Zúñiga, a healthy, middle-aged father who socializes at least six hours a day and has a few good friends he can count on. He sleeps at least seven hours most nights, walks to work, and eats six servings of fruits and vegetables most days. He works no more than 40 hours a week at a job he loves with co-workers he enjoys. He spends a few hours every week volunteering; on the weekends he worships God and indulges his passion for soccer. In short he makes daily choices that favor happiness, choices made easier because he lives among like-minded people in the verdant, temperate Central Valley of Costa Rica.

Dan Buettner, a New York Times best-selling author, has been exploring what makes us healthy and happy for the past 15 years. His fourth book, The Blue Zones of Happiness, just published by National Geographic, is available wherever books are sold.

Sidse Clemmensen is another possible candidate. With a loving partner and three young children, she lives in a tightly knit cohousing community with other families who share chores, childcare, and meals in a communal kitchen.

She’s a sociologist, a job that challenges and engages her every day. She and her family bicycle to work, the store, and the children’s school, which helps keep them fit. She pays high taxes on her modest salary but gets health care and education for her family, as well as guaranteed retirement income.

In Aalborg, Denmark, where she lives, people feel confident the government will make sure that nothing too bad happens to them.

And then there is Douglas Foo. A successful entrepreneur, he drives a $750,000 BMW and lives in a $10 million house. He’s married, with four well-behaved children who excel at school. He put himself through school working four jobs and started a company that eventually grew into a $59 million multinational enterprise.

He works about 60 hours a week between his business and his philanthropic pursuits. He’s earned the respect of his employees, peers, and the larger community. He’s worked hard to achieve his success, but as Foo readily admits, he probably couldn’t have created this life anywhere other than Singapore.

PHOTOGRAPH BY ROBERT HARDING, AURORA

Zúñiga, Clemmensen, and Foo illustrate three different strands of happiness that braid together in complementary ways to create lasting joy.

I call them pleasure, purpose, and pride. They also live in countries that encourage those strands. By meeting each of these people and exploring their home countries, we’ll discover the secrets to what makes the people in these places so much happier than those in other places.

Consider Zúñiga, who like many Costa Ricans enjoys the pleasure of living daily life to the fullest in a place that mitigates stress and maximizes joy.

Scientists call his type of happiness experienced happiness or positive affect. Surveys measure it by asking people how often they smiled, laughed, or felt joy during the past 24 hours.

His country is not only Latin America’s happiest; it’s also where people report feeling more day-to-day positive emotions than just about any other place in the world.

Clemmensen represents a brand of happiness typified in the purpose-driven life of Danes. Like all forms of happiness, it assumes basic needs are covered so that people can pursue their passions at work and leisure.

Academics refer to this as eudaimonic happiness, a term that comes from the ancient Greek word for “happy.” The concept was made popular by Aristotle, who believed that true happiness came only from a life of meaning—of doing what was worth doing.

Gallup measures this by asking respondents whether they “learned or did something interesting yesterday.” In Denmark, a country that has most consistently topped Europe’s happiness rankings for the past 40 years, society has evolved to make it easy to live an interesting life.

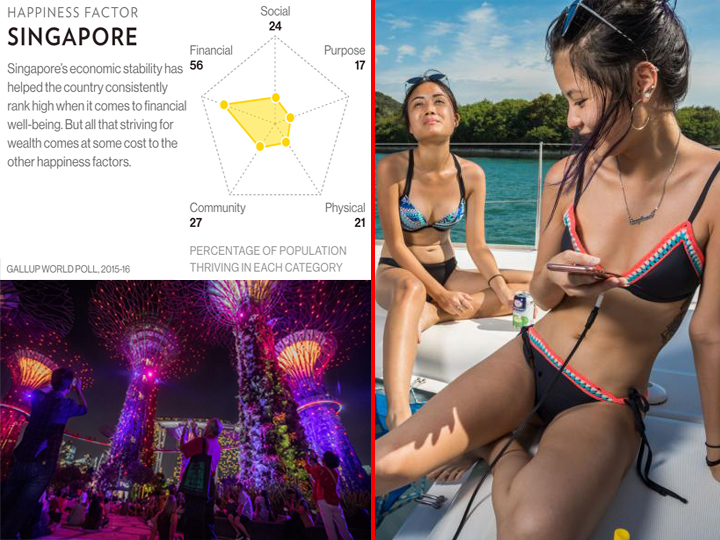

And true to Singapore’s reputation for having a semi-fanatical drive for success, Foo—with all his ambition and accomplishments—represents the “life satisfaction” strand of happiness.

Social scientists often measure this type of happiness by asking people to rate their lives on a scale of zero to 10. Experts also call this evaluative happiness.

Internationally it’s considered the gold standard metric of well-being. Singapore has most dependably ranked number one in Asia for life satisfaction.

PHOTOGRAPH BY CORY RICHARDS

The researchers who publish the annual World Happiness Report found that about three-quarters of human happiness is driven by six factors: strong economic growth, healthy life expectancy, quality social relationships, generosity, trust, and freedom to live the life that’s right for you.

These factors don’t materialize by chance; they are intimately related to a country’s government and its cultural values.

In other words, the happiest places incubate happiness for their people.

To illustrate the power of place, John Helliwell, one of the report’s editors, analyzed 500,000 surveys completed by immigrants who’d moved to Canada from 100 countries over the previous 40 years, many from countries considerably less happy.

Remarkably Helliwell and his colleagues discovered that, within a few years of arriving, immigrants who came from unhappy places began to report the increased happiness level of their adoptive home. Seemingly their environment alone accounted for their increased happiness.

Zúñiga, Clemmensen, and Foo pursue their goals intensely, but not at the expense of joy and laughter, and they look with pride on what they are doing and what they have already accomplished.

They’re able to do this, in many cases, because the places where they live—their nations, communities, neighborhoods, and family households—give them an invisible lift, constantly nudging them into behaviors that favor long-term well-being