No, it was not the FBI that locked the screens of computer users and demanded payment for fines as the ransomware known as Reveton claimed on the machines it infected.

But it was the work of the FBI, along with federal and international partners, that helped lock up one of the people involved in the scheme.

Raymond Uadiale, of Maple Valley, Washington, didn’t create or spread the malware, but he helped its distributor cash out and launder the payments made by victims after taking some of the profit for himself. For his part in the crime, Uadiale pleaded guilty to conspiracy to commit money laundering and will spend 18 months in prison.

“He was the one who helped keep it going,” said Special Agent Christopher Rizzo, who investigated the case from the FBI’s Washington Field Office. “It would not have been profitable without his role in it.”

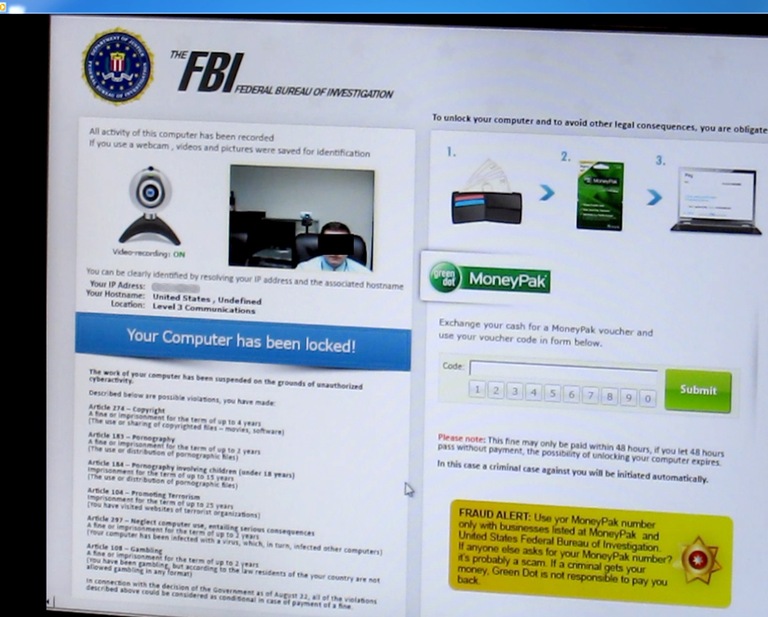

Computer users who inadvertently downloaded the ransomware would find their computers locked behind a splash screen claiming they had violated federal laws by visiting illicit websites or downloading illegal files. These screens would display the logo of the FBI or another law enforcement entity along with false threats of legal action.

Rizzo said that the ransomware distributor would often place the malware on pornographic websites so that the affected computer user was more likely to believe the ransomware’s threats.

“By infecting some of the ad space on a site, a user can get the ransomware just by being on that page,” Rizzo said. This type of “drive-by infection” is hard to detect and avoid.

The ransomware victims were told that to avoid arrest, they needed to purchase a GreenDot MoneyPak to pay a fine, typically $200-400, and type the card’s serial number into the screen.

MoneyPaks are available at many mass retailers and are as flexible as cash, allowing the recipient to transfer the money loaded onto the MoneyPak onto any pre-paid credit or debit card.

Armed with the MoneyPak serial numbers, the ransomware’s distributor would move the money onto debit cards that Uadiale could cash out at an ATM.

Uadiale kept about 30 percent of each transaction for himself and sent the balance back to the United Kingdom-based malware distributor, mostly through the now-defunct digital currency processor Liberty Reserve.

Rizzo said that Uadiale cleared a total of about $100,000 and was not the only one assisting the malware’s maker. Seeing the numbers involved make the financial motivation behind these crimes all the more clear.

“The FBI would never remotely lock someone’s computer. If you were truly under investigation, you would hear from us very directly. Our advice is, don’t pay the ransom.”

Christopher Rizzo, special agent, FBI Washington Field

Victims of the Reveton ransomware would find their computers locked behind a screen like this that falsely informed them they were being fined for illegal activity.

“The FBI would never remotely lock someone’s computer,” stressed Rizzo. “If you were truly under investigation, you would hear from us very directly. Our advice is, don’t pay the ransom.”

Other advice from Rizzo: Take the time to learn how to protect your computer and network and institute a reliable file backup system. He recommends an external drive that backs up on a pre-programmed regular schedule but is not constantly connected to your computer or network.

Once the FBI was aware of the ransomware, they began collecting data and evidence from victim computers.

Working with the U.K.’s National Crime Agency, the FBI was able to identify the source of the malware and secure a warrant to search his computers. From those machines, investigators learned more about those who aided the effort, including Uadiale. The malware creator’s trial is still pending in the United Kingdom.

Rizzo has worked on several ransomware cases and many of the cases involved more sinister and damaging variants of the malware. “We take them all very seriously,” said Rizzo of these cybercrimes. “But the fact that our logo and name were being used in this one—we took that personally.”

How to Avoid Being a Victim of Ransomware

Understand

Ransomware is a type of malicious software or malware. A user can inadvertently download it onto a computer by opening an e-mail attachment, clicking on an ad, or even visiting a website that is seeded with the malware.

Once the infection is present, the malware will lock up the computer.

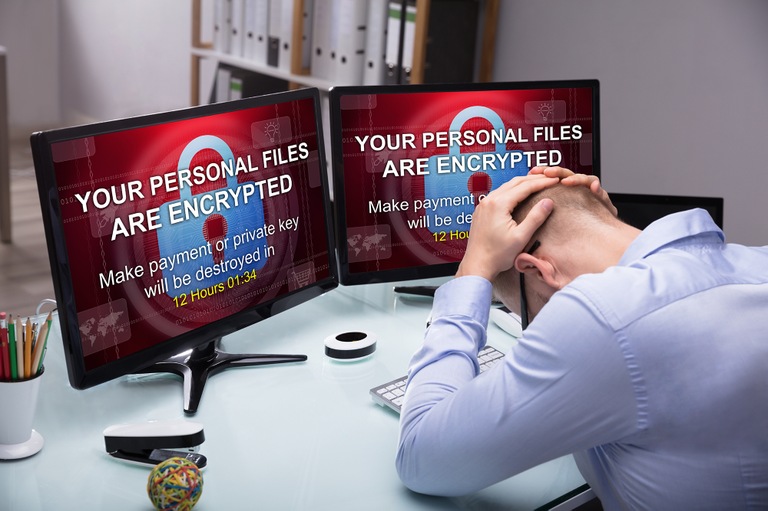

More menacing versions can encrypt files and folders on local drives, any attached drives, backup drives, and potentially other computers on the same network. Users discover they’ve been infected when they can no longer access their data or see computer messages advising them of the attack and making ransom demands

Prevent

The best way to avoid being exposed to malware is to be a cautious and conscientious computer user. Malware distributors have gotten increasingly savvy, and computer users need to be even more wary of e-mail links, e-mail attachments, online ads, and even some websites.

In addition, computer users should:

- Keep operating systems, software, and firmware current and up to date.

- Ensure antivirus and anti-malware solutions are set to automatically update and conduct regular scans.

- Back up data regularly with a secure backup system that is unconnected to the computers and networks is backing up.

Respond and Report

The FBI doesn’t support paying a ransom in response to a ransomware attack. If you are a victim of ransomware, go to a computer professional to remove the malware completely and report it to the Internet Crime Complaint Center, or IC3, at ic3.gov. The IC3 is a partnership between the FBI and the National White-Collar Crime Center.