JUST SAYING

BY RAUL HERNANDEZ

NOTEBOOKVENTURA

Biden Picks Harris

I applaud presidential candidate Joe Biden’s selection of Sen. Kamala Harris.

But the bottom line, I’d vote for Biden if his VP pick was a bread box.

Let’s say I am not comfortable with a psychopath, lying con man walking around with the nuclear codes in his pocket.

Let’s say I am not comfortable with a psychopath, lying con man walking around with the nuclear codes in his pocket.

It is like allowing a 5-year-old to play with matches at a downtown gasoline station. Sooner or later if an adult doesn’t intervene, the station is going to explode and a few downtown blocks are going to be wiped out.

If Trump gets another four years, sooner or later, he is going to incinerate the world or get America into a major conflict where thousands of American service members come home in body bags.

Trump is the benefactor of pure hate and blind ignorance that went to the polls.

I published this column in July 2016, and it is worth publishing it, again. This is one of the most informative and insightful columns I have published in my column because it comes from solid legal sources. It is a playbook for how cops find ways to skirt a person’s right to remain silent. Clip and save this column:

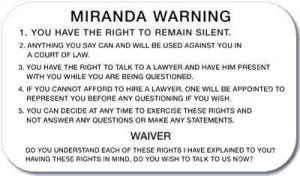

A playbook for how cops can legally tap dance around giving a suspect his Miranda rights and still not violate his constitutional rights was recently spelled out in a law enforcement magazine by a prosecutor.

It was interesting reading to say the least, eye-opening.

First, the FBI reported that before cops were required to read suspect their Miranda rights, police officers cleared 63 percent of violent crimes. After the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that suspects must be told they had a right to remain silent, the average plummeted to 45 percent, according to Police — The Law Enforcement Magazine.

First, the FBI reported that before cops were required to read suspect their Miranda rights, police officers cleared 63 percent of violent crimes. After the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that suspects must be told they had a right to remain silent, the average plummeted to 45 percent, according to Police — The Law Enforcement Magazine.

Police magazine noted that given the numbers of reported crimes and this known reduction in clearance capability, we can reliably say that Miranda has resulted in the inability to clear a quarter-million homicides, 1 million rapes, 5 million robberies, and 9 million aggravated assaults.

But in the 48 years since Miranda was decided, the Supreme Court tweaked its ruling in 55 decisions to reduce the impact of their landmark decision.

But in the 48 years since Miranda was decided, the Supreme Court tweaked its ruling in 55 decisions to reduce the impact of their landmark decision.

The article in Police Magazine does an excellent job on explaining how cops are still getting convictions.

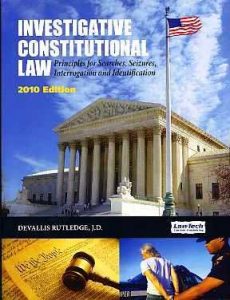

It was published earlier this year by Devallis Rutledge is a former police officer and veteran prosecutor who currently serves as special counsel to the Los Angeles County district attorney.

Rutledge is the author of 12 books, including “Investigative Constitutional Law: Principles for Searches, Seizures, Interrogation and Identification.” The book comes with a big price tag, $85.

Rutledge is the author of 12 books, including “Investigative Constitutional Law: Principles for Searches, Seizures, Interrogation and Identification.” The book comes with a big price tag, $85.

Voluntary Stationhouse Interrogations

If you can safely delay arresting a suspect or subjecting him to custodial restraints, you can delay triggering Miranda. If your suspect is not a flight or safety risk, consider inviting him or her to the station to talk, as officers did in two of the Supreme Court’s impact-reducing cases, Rutledge wrote.

In Oregon v. Mathiason, a burglary suspect agreed to come to the station voluntarily. He was told he was not under arrest, and was treated accordingly. Without warnings, he confessed to the crime.

The Supreme Court held that Miranda did not apply, because Mathiason was not in custody during the questioning. Said the court, “Police officers are not required to administer Miranda warnings to everyone they question. Nor is the requirement of warnings to be imposed simply because the questioning takes place in the station house, or because the questioned person is one whom the police suspect,” Rutledge stated.

The Supreme Court repeated this ruling in California v. Beheler, a case in which officers asked a murder suspect to come to the station, told him that he was not under arrest, and made it clear he was free to leave whenever he wanted. The court held that Miranda did not apply, and Beheler’s confession was admissible against him.

When taking advantage of these two rulings, it’s advisable to tell the suspect at the outset, “You’re not under arrest. You’re free to leave at any time.” After he confesses to the crime, you’re free to change your mind and arrest him.(Stansbury v. California)

Undercover Questioning

Here is what Rutledge wrote about what cops are able to do:

“If a voluntary station house interrogation is not a practical option and the circumstances require you to take the suspect into custody, consider delaying overt interrogation while trying covert questioning by an undercover officer, posing as a fellow prisoner.

In Illinois v. Perkins, officers placed their arrestee into a cell where an undercover officer, wearing jailhouse clothes, engaged him in conversation. The suspect’s unwarned statements were admissible, because there is no compulsion to speak to a perceived fellow prisoner.

The Supreme Court said this: “An undercover officer posing as a fellow inmate need not give Miranda warnings to an incarcerated suspect before asking questions that may elicit an incriminating response. Miranda does not forbid strategic deception by taking advantage of a suspect’s misplaced trust.”

Particularly in the more serious cases where suspects are more likely to invoke,Perkins often provides a legitimate means to reduce Miranda’s impact, according to Rutledge.

Prepare the cell in advance, with audio and video recording if possible, and brief your undercover officer as to the details he needs to cover. This technique produces admissible statements in homicides and other serious cases more often than you might think.

Strategic Deception at Arrest

The Supreme Court has held that you can lawfully arrest for any crime as to which you have probable cause in Devenpeck v. Alford.

This means you do not have to tell a suspect he is under arrest on the most serious charge you could support, but may initially arrest him for something less serious, giving him less incentive to invoke Miranda. If he then waives, you’re free to question him about any crime you suspect he may have committed.

In Colorado v. Spring, ATF agents arrested a man for a firearms violation, even though he was also suspected of murder. Given Miranda warnings, he waived and talked about the firearms offense. Agents then asked if he had ever shot anyone, and he admitted that he “shot a guy once.” This admission was used to convict him of murder.

Rejecting Spring’s argument that the agents should have warned him of all the crimes he was going to be questioned about, the Supreme Court said the following: “A suspect’s awareness of all the crimes about which he may be questioned is not relevant to determining the validity of his decision to waive the Fifth Amendment privilege.

Mere silence by law enforcement officers as to the subject matter of an interrogation is not ‘trickery’ sufficient to invalidate a suspect’s waiver of Miranda rights.”

The Spring decision can reduce the impact of Miranda on your chances of getting a waiver and a statement, if you simply arrest your suspect for a less serious crime, take a waiver, and gradually expand your interrogation into the facts of the more serious crime.

Following interrogation, you’re free to book on the more serious charges.

Implied Waivers

Twice, the Supreme Court has held that there is no requirement to ask the suspect if he wants to waive his rights.

In North Carolina v. Butler, the court said that “an explicit statement of waiver is not invariably necessary,” and that Miranda waivers may also be implied from the fact that a warned suspect answers questions or makes a statement.

Berghuis v. Thompkins held that if a suspect is fully warned and acknowledges that he understands the rights, it isn’t necessary for officers to ask him if he wants to talk.

Said the court, “If the State establishes that a Miranda warning was given and that it was understood by the accused, an accused’s uncoerced statement establishes an implied waiver. After giving a Miranda warning [including acknowledgment of understanding], police may interrogate a suspect who has neither invoked nor waived Miranda rights,” according to Rutledge.

Needlessly asking a warned suspect whether he wants to talk gives him an opportunity to invoke by simply saying, “No.”

But if you dispense with this unnecessary question and simply start talking to him after the warning and acknowledgment, he is more likely to answer some engaging, non-threatening question, thereby establishing his implied waiver and allowing interrogation to continue, according to Rutledge.

State Variations

Although states can create greater restrictions on interrogations than Miranda imposes, they cannot do so on the basis of Miranda.

Instead, they must rely on state statutes or constitutions. “A state court can neither add to nor subtract from the mandates of the United States Constitution,” upon which Miranda is based. (North Carolina v. Butler)