In February 2020, Friedrich Karl Berger, 95, was ordered removed from the U.S. based on his participation in Nazi-sponsored persecution while serving in Nazi Germany in 1945 as an armed guard of concentration camp prisoners in the Neuengamme Concentration Camp system (Neuengamme), according to authorities.

In February 2020, Friedrich Karl Berger, 95, was ordered removed from the U.S. based on his participation in Nazi-sponsored persecution while serving in Nazi Germany in 1945 as an armed guard of concentration camp prisoners in the Neuengamme Concentration Camp system (Neuengamme), according to authorities.

“Berger’s removal demonstrates the Department of Justice’s and its law enforcement partners’ commitment to ensuring that the United States is not a safe haven for those who have participated in Nazi crimes against humanity and other human rights abuses,” said Acting Attorney General Monty Wilkinson.

Adding, “The Department marshaled evidence that our Human Rights and Special Prosecutions Section found in archives here and in Europe, including records of the historic trial at Nuremberg of the most notorious former leaders of the defeated Nazi regime. In this year in which we mark the 75th anniversary of the Nuremberg convictions, this case shows that the passage even of many decades will not deter the Department from pursuing justice on behalf of the victims of Nazi crimes.”

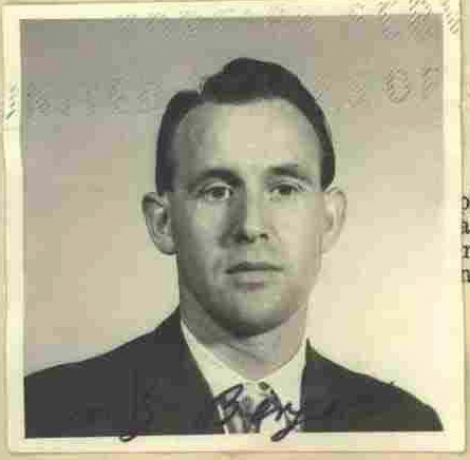

Friedrich Karl Berger (1959)

In November 2020, the Board of Immigration Appeals upheld a Memphis, Tennessee, Immigration Judge’s Feb. 28, 2020, decision that Berger was removable under the 1978 Holtzman Amendment to the Immigration and Nationality Act because his “willing service as an armed guard of prisoners at a concentration camp where persecution took place” constituted assistance in Nazi-sponsored persecution.

The court found that Berger served at a Neuengamme sub-camp near Meppen, Germany, and that the prisoners there included “Jews, Poles, Russians, Danes, Dutch, Latvians, French, Italians, and political opponents” of the Nazis.

The largest groups of prisoners were Russian, Dutch and Polish civilians.

After a two-day trial in February 2020, the presiding judge issued an opinion finding that Meppen prisoners were held during the winter of 1945 in “atrocious” conditions and were exploited for outdoor forced labor, working “to the point of exhaustion and death.”

The court further found, and Berger admitted, that he guarded prisoners to prevent them from escaping during their dawn-to-dusk workday, on their way to worksites and on their way back to the SS-run subcamp in the evening.

At the end of March 1945, as allied British and Canadian forces advanced, the Nazis abandoned Meppen.

The court found that Berger helped guard the prisoners during their forcible evacuation to the Neuengamme main camp – a nearly two-week trip under inhumane conditions, which claimed the lives of some 70 prisoners.

The decision also cited Berger’s admission that he never requested a transfer from concentration camp guard service and that he continues to receive a pension from Germany based on his employment in Germany, “including his wartime service.”

In 1946, British occupation authorities in Germany charged SS Obersturmführer Hans Griem, who had headed the Meppen sub-camps, and other Meppen personnel with war crimes for “ill-treatment and murder of Allied nationals.” Although Griem escaped before trial, the British court tried and convicted other defendants of war crimes in 1947.

Since the 1979 inception of the Justice Department’s program to detect, investigate, and remove Nazi persecutors, it has won cases against 109 individuals.

Over the past 30 years, the Justice Department has won more cases against persons who participated in Nazi persecution than have the law enforcement authorities of all the other countries in the world combined.