The hype shortly preceding its release was that the movie “Platoon” was “the most realistic movie ever made about the Vietnam War’ – ever.

Platoon got an Academy Award for Best Picture of 1986, and Platoon’s director Oliver Stone was awarded the Academy’s Best Director nod. Stone wrote the script based on his experiences as an infantryman in Vietnam.

Ignacio Medina, however, wasn’t impressed with Stone’s tale of betrayal and murder in the jungles of Vietnam, not at all.

“People who have never been to Vietnam might think it is a good movie because of the action. A good 50 percent of the movie is nothing but baloney,” said Mr. Medina. “It is not realistic – especially the combat situations they show in the film.”

That is what he told the El Paso Herald-Post 27 years ago when he agreed to review it for the newspaper, and the movie was just being released across the nation.

Mr. Medina wasn’t a movie critic looking at Platoon through the sterilized filter of a Hollywood lens. His thick military resume noted credentials and experience: Served in World War II, Korea and three tours of Vietnam. Two of those tours with the 25th Infantry Division, which was the combat unit depicted in Platoon.

In Vietnam, he was awarded the Silver Star for bravery on the battlefield. Before retiring, he attained the highest rank that a non-commissioned officer can get in the Army, command-sergeant-major. Before retiring he was stationed at Fort Bliss in El Paso, Texas.

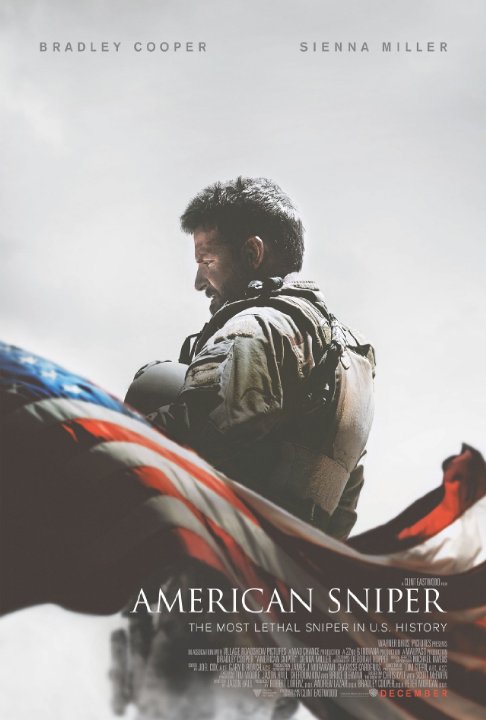

Now comes the movie, “American Sniper,” a biographical war film about Navy Seal Chris Kyle who wrote the book, “American Sniper: The Autobiography of the Most Lethal Sniper in U.S. Military History,” that the movie was based on.

The film stars Bradley Cooper and was directed by Clint Eastwood. The movie has been nominated as the Best Picture for 2014.

Basically, Kyle protected U.S. troops who were sweeping through villages along with performing other dangerous assignments in Iraq.

Some say the movie was politicized. Others argue it is about an American hero.

The critics gave American Sniper mixed review but most liked the movie, according to Rotten Tomatoes.

Under the headlines: “American Sniper’ Is Almost Too Dumb to Criticize,” Rolling Stone’s Matt Taibb wrote:

“It’s usually silly to get upset about the self-righteous way Hollywood moviemakers routinely turn serious subjects into baby food,” Rolling Stone magazine wrote about American Sniper.

Under the headlines, “Marine’s Response to Critics of ‘American Sniper’ Is 1,851 Words. It’s Worth It to Read Each One,” a marine criticized the reviewers.

“…the film was about a man on the ground and the struggle to come home with a head full of grief and regret, not the Iraq war itself,” the Marine wrote.

The media talking heads who recently analyzed all the fine points in the politics of giving children measles’ vaccinations, have now shifted into the “taste great” and “less filling” mode in scrutinizing American Sniper.

CNN just devoted a whole hour on a special about American Sniper, pouring out intellectual, philosophical and prophetic insights about the movie and Bradley Cooper’s character.

What the movie did that was positive was brought attention to post traumatic stress disorder.

Otherwise, it is a movie. It is first and foremost, entertainment. Much of it real. Much of it, however, is Clint Eastwood, like any good director, selling tickets by cramming a complex issue into two hours and 14 minutes of fast-paced action.

Medina Goes to the Movies

When the El Paso Herald-Post newspaper editors were looking for a Vietnam veteran, preferably one who had served with the 25th Infantry Division, to review “Platoon,” I suggest Mr. Medina who bled Army green to be their camouflaged Roger Ebert, so to speak.

The editors accepted my suggestion. Now, I had to convince Mr. Medina.

But first, in the interest of full disclosure, I told the editors that Mr. Medina was one of my best friends, Art Molina’s, step-father. Mr. Medina was like my surrogate father too. My father Juan Hernandez had also served in three wars – World War II, Korea and two tours of Vietnam with the U.S. Army. So, my father, like Mr. Medina , was often away from home.

This meant that Art, Art’s cousin and my other best friend, David Andrade, and I were always getting into predicaments, much of it stemmed from smuggling cheap booze across the border from Juarez to party on weekends or crossing the bridge to J-Town from time to time to go bar hopping along with hundreds of other under-aged youngsters from El Paso.

I believed Mr. Medina would also do a good job reviewing Platoon because he was a good role model for Art, David and I: He drank beer, didn’t like people to lie to him and most of all, he didn’t mince words. He also got the three of us out of several jams.

Nonetheless, the price for cleaning up some of our screw ups was a tongue lashing.

Cleaning the language and adding a look of disgust, he’d say something like this to Art, David and I after he heard our lame excuses: “You guys can’t keep your stories straight. And, you think I am an idiot.”

Mr. Medina, a wiry and fearless man, reminded me of the “Apocalypse Now” character Lt. Colonel Bill Kilgore played by Robert Duval whose classic line in that movie was: “I love the smell of napalm in the morning.”

I once asked Mr. Medina why he kept volunteering to go to Vietnam? He said simply: “That’s my job.”

Paused and calmly added, “And, the pay is good.”

You Write the Review

The problem with the Platoon movie review, is Mr. Medina didn’t go to the movies because he thought that most weren’t worth 120 minutes of his time. Still, he liked to watch old John Wayne movies.

Agitated after I told him he had to write the Platoon movie review, he said: “I’m not going to write all that stuff. You write it. You can interview me. That’s what you get paid to do.”

The newspaper decided that I would write the story as a movie review, which would appear on the front page, but the review would be written under Ignacio Medina’s byline “as told to Raul Hernandez” – moi.

So, basically, I served as Mr. Medina’s tape recorder, and just jotted down what he told me, asking a few questions along the way to smooth out the Platoon interview.

Anyway, I went to the movies with Mr. Medina who didn’t like popcorn, didn’t want a soda and walked into the movie theater like he had just landed on the moon.

I also recall that Vietnam veterans were told that counselors would be available by calling a certain number after they watched Platoon and if they needed to talk to someone.

A real war movie had to have real counselors.

Here is some of what Mr. Medina told me back then about Platoon:

- “I never saw one GI shoot another GI just because he couldn’t get along with him. Violence among the soldiers almost didn’t exist especially when they went out in the jungle on a mission or patrol. They were as close to each other as brothers, trying to stay alive and accomplish the mission.”

- “There were search and destroy missions through the villages. But when they got near the villages, usually they would estimate what kind of enemy force was in that village before going in. They would level the village with 500 or 1,000 rounds if they got enemy resistance. There were isolated incidents of massacres in villages.”

- “I got upset (by the movie) because it happened to be the 25th Infantry Division. I had experience with both battalions with the division, the “Wolfhounds” and the “Bobcats.” I never saw anybody fighting among themselves like they did in the movie.”

- “You didn’t have the fragging until after 1969 when the drug situation got out of hand. Fragging happened everywhere in Vietnam, in fighting units as well as the support units based in the rear areas.”

- “The only regret that I have is that this movie was representing the men who served with the 25th Division in Vietnam, wearing the ‘Tropical Lightning’ patch. The majority of the men who served with that division would say that the movie was not an accurate portrayal.”

Forrest Gump and John Wayne

I am glad that the newspaper didn’t send Mr. Medina to review the Vietnam footage of the movie “Forrest Gump,” and as much as he liked John Wayne movies, I know Mr. Medina didn’t believe “The Horse Soldiers” was an accurate portrayal of the Civil War either.

I had problems with the movie Platoon because all the characters were black and white soldiers. The lone Hispanic character had a religious altar next to his bunk where he prayed and was relegated to two or three sentences in Stone’s “the real Vietnam” script.

This was Stone’s Vietnam.

According to the Department of Defense, there are no numbers to indicate how many Hispanics served in Vietnam because we were lumped in with Caucasians. However, people with Hispanic surnames comprised 5.5 percent of the casualties in Vietnam and 4.5 percent of the 1970 population were Hispanics.

So Hispanics were over represented in the casualty department.

I kept thinking that Stone must have bumped into a few Hispanics when he was in Vietnam.

Veterans Who Served Their Country

Years ago, Mr. Medina and my dad were buried at Fort Bliss National Cemetery.

Veterans like Mr. Kyle, Mr. Medina and my father and millions of others served this country with honor and pride and each had his own, unique story and experiences like Mr. Kyle. He was a Navy Seal, a tremendous accomplishment.

Last week, I again watched on Netflix the World War II documentary series by producer Ken Burns. Much of it was narrated by frail, gray-haired veterans who fought in that war.

I saw young marines getting off the ships only to get mowed down at some God-forsaken beach in the middle of the Pacific, and a freezing GI with a thousand-mile stare and a rifle in a foxhole at the Battle of the Bulge.

I thought about my Dad and Mr. Medina who rarely spoke about war as I watched the series. The documentary offers more than the empty calories of some meaningless, feel-good Hollywood war script.

The words and images in the documentary are powerful, and it is the real deal.

“The greatest sense I had about the war was that it was over and we’d never have to do this again. But I also had a sense kinship with all the other guys who had been in the service. Somehow we had been a separate entity from the people who were civilians,” Bill Langsford, a Marine who served in the Pacific, said in the documentary. “Our feeling was like we were like our own gang. We had all done what we were told to do. We were characterized as heroes. But we weren’t heroes. We were just guys who were there and did what we were suppose to do.”